Erwin Kräutler – Right Livelihood Award

www.rightlivelihood.org/krautler.html

www.cimi.org.br (CIMI)

http://plattformbelomonte.blogspot.com

www.survivalinternational.org/news

The Right Livelihood Award, established in 1980 by Jakob von Uexkull, is an award that is presented annually, in early December, to honour those „working on practical and exemplary solutions to the most urgent challenges facing the world today“. An international jury, invited by the five regular Right Livelihood Award board members, decides the awards in such fields as environmental protection, human rights, sustainable development, health, education, and peace. Read More: > HERE <

Erwin Kräutler CPPS, auch Dom Erwin, (* 12. Juli 1939 in Koblach, Vorarlberg) ist römisch-katholischer Bischof und Prälat von Xingu, der flächenmäßig größten Diözese Brasiliens. 2010 wurde sein Einsatz für die Rechte der Indios und die Erhaltung des Amazonas-Urwalds mit dem alternativen Nobelpreis ausgezeichnet. Read More: > HERE <

Erwin Kräutler, a Catholic Bishop motivated by liberation theology, is one of Brazil’s most important defenders of and advocates for the rights of indigenous peoples. Already in the 1980s, he helped secure the inclusion of indigenous peoples‘ rights into the Brazilian constitution. He also plays an important role in opposing one of South America’s largest and most controversial energy projects: the Belo Monte dam.

Kräutler was born in Austria on July 12th, 1939, became a priest in 1965 and shortly after went to Brazil as a missionary. In 1978, he became a Brazilian citizen (though also keeping his Austrian citizenship). He worked among the people of the Xingu-Valley, who include indigenous peoples of different ethnic groups. In 1980, Kräutler was appointed Bishop of Xingu, the largest diocese in Brazil. From 1983-1991, and since 2006 he is the President of the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) of the Catholic Church in Brazil.

Kräutler is motivated in his work by the teachings of liberation theology. He teaches that a Christian has to take the side of the powerless and to oppose their exploiters.

Working for indigenous peoples‘ rights – For five centuries, the population of Brazil’s indigenous peoples has constantly decreased – and the downward trend still continues. Today the causes are well-known and documented, including direct (yet rarely investigated) violence in connection with the appropriation of indigenous land; land grabs for energy, settlement, mining, industry, farming, cattle, and agribusiness projects; and military projects for national security that aim to open up areas.

During Kräutler’s presidency, CIMI has become one of the most important defenders of indigenous rights, with a focus on land rights, self-organisation and health care in Indian territories. In 1988, CIMI’s intensive lobbying helped secure the inclusion of indigenous people’s rights in the Brazilian Constitution. The Council has also raised awareness within the Church about indigenous people’s issues and rights.

Since 1992 and besides CIMI’s advocacy work, Kräutler has continued working tirelessly for the Xingu on the ground. The projects he has initiated include building houses for poor people, running schools, building a facility for mothers, pregnant women and children, founding a ‚refugio‘ for recuperation after hospital treatment, emergency aid, legal support, and work on farmers‘ rights and land demarcation.

Opposing the Belo Monte dam – For 30 years, Kräutler has been very active in the struggle against the plans for the huge Belo Monte dam on the Xingu River, nowadays heavily promoted by President Lula, which would be the third largest dam in the world. The dam would destroy 1000 square km of forest, flood a third of the capital city, Altamira, and create a lake of stagnant, mosquito-infested water of about 500 square km, which would make life in the rest of the city very difficult. 30,000 people would have to be relocated.

In 1989 the World Bank pulled out of a plan to build a series of huge hydroelectric dams on the Xingu River in the centre of Brazil. The dams were judged a potential social and environmental catastrophe, highlighted by the largest combined demonstration by the indigenous tribal people of the area ever staged. This is the same battle which is being supported by Avatar director James Cameron and actress Sigourney Weaver.

-

Even like Xingu River the largest water distribution of Amazonas, also Yamuna River for Ganges River, the consequences about non enviromental assessment creating negativ enviromental impacts, loss of biodiversity and cultural heritage. Scientists round the globe sounding Alarm about the freshwater qualities and Rivers.

http://amazonwatch.org/tour-belo-monte

Ten years after the World Commission on Dams (WCD) report, the WCD is still our best roadmap towards ensuring that future dams minimize social and environmental impacts, the legacy of existing dams are addressed, and affected people directly benefit from the projects. Watch this video, produced by International Rivers and EcoDoc Africa, to learn more about the promise of the WCD. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Commission_on_Dams

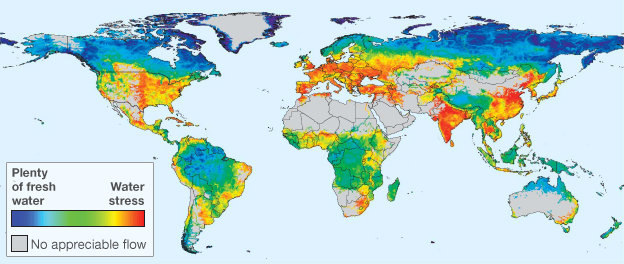

Water map shows billions at risk of ‘water insecurity’ – About 80% of the world’s population lives in areas where the fresh water supply is not secure, according to a new global analysis.Researchers compiled a composite index of “water threats” that includes issues such as scarcity and pollution.

The most severe threat category encompasses 3.4 billion people.Writing in the journal Nature, they say that in western countries, conserving water for people through reservoirs and dams works for people, but not nature.They urge developing countries not to follow the same path.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11435522

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drinking_water

http://www.iaia.org/ Conference Theme – What are the consequences to ecosystems, cultural heritage and human well-being -in the short and long run- of decisions taken by infrastructure developers, industry executives and managers, financial agents and business leaders?

Today we know much more about the environmental and social effects related to decisions taken in these sectors and their implications to humankind, especially the… poorest and most defenseless people.Impact assessment comprises a set of tools that strengthen the sense of responsibility in business and investments and in the design and execution of policies, plans, programs and projects.

Responsible development means to assess in an integral way the impacts on the environment and on communities, human health, and well-being. Infrastructure and industrial projects as well as business undertakings (in the financial and retail sectors, for instance) should be developed under this responsible point of view, from the early conceptual stage of each project until the end of its utilitarian life.Since we share a common world, we should be able to identify common objectives for responsible development, in which each sector of the economy becomes aware of the effects of its decisions.

Areas of interest will include:

Energy

Corporate social responsibility

Water and coastal zone management

Climate change (mitigation and adaptation)

Cultural heritage

Transportation

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries

Extractive industry

Sustainable production and consumption

Tourism

Integrated project appraisal

Land use planning

Health and pharmaceutical sectors

Public health and community development

Indigenous knowledge in impact assessment

Environmental impact of trade agreements

Environmental practice and governance in Latin America and the Caribbean

Environmental compliance and enforcement

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_impact_assessment

At IAIA11, Mexico, ideas and experiences on this theme will be shared by experts from around the globe, with the end result being a better collective knowledge about how to ensure a better future.Conference TopicsIAIA11 participants will be encouraged to highlight how the various instruments of impact assessment can assist infrastructure developers, industry, decision-makers, financial institutions, retail development, development cooperation providers, and the public.

An environmental impact assessment (EIA) is an assessment of the possible impact—positive or negative—that a proposed project may have on the environment, together consisting of the natural, social and economic aspects.

The purpose of the assessment is to ensure that decision makers consider the ensuing environmental impacts when deciding whether to proceed with a project. The International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) defines an environmental impact assessment as “the process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social, and other relevant effects of development proposals prior to major decisions being taken and commitments made.”

After an EIA, the precautionary and polluter pays principles may be applied to prevent, limit, or require strict liability or INSURANCE COVERAGE to a project, based on its likely harms. Environmental impact assessments are sometimes controversial.

http://www.ilovemountains.org/ , www.google.com/earth/index.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_impact_assessment

http://gangaahvaan.org/home , http://www.minesandcommunities.org/

http://www.truth-out.org/ It’s a go. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio „Lula“ da Silva just signed an agreement to build the Belo Monte dam on the Xingu River. It will be large: 3.75 miles of hulking concrete and 11,000 megawatts of power, enough energy to power 23 million homes. It will be the third-largest dam in the world, and is the very clear Brazilian answer to the question: Where will the 21st century’s energy come from? Dams are boasted as the best, cleanest, most sustainable response to that question, a far better option than decapitating the Appalachians, turning the Blue Ridge Mountains of West Virginia and the Cumberlands of Kentucky into wastelands.

Thus greenwashed, construction companies in the third world pour concrete as fast as they can mix it, while Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) credits pile up in the accounts of their governments. It makes for a neat-sounding plan: third world economic development gets powered by an infinitely renewable energy source, with salable credits from Western industrialized countries paying for the construction costs – clean capitalism for the planet. A neat plan, until you look a little closer, close enough to see the nitty-gritty substance. That’s where the trouble starts. Dams work by pushing pressurized water through turbines. That water spins them at enormous speed, creating energy. But how to pressurize the water? By building tremendous concrete barricades behind which it piles up in man-made lakes.

That’s where the trouble begins. Earthquake-inducing weaponry was long the province of science fiction writers, the object of Nikola Tesla’s feverish jottings about the „art of telegeodynamics.“ Turns out it could be done, although not the way the more imaginative had envisioned. The sheer volume of water stored behind concrete dam walls can be so sizable as to actually cause seismic activity by affecting the stability of tectonic plates. Chinese scientists have implicated the Zipingpu Dam in the Sichuan earthquake of May 2008, in which perhaps 80,000 people died. Other scientists warn that the titanic Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze could likewise cause tremors.

That would just be one more problem stemming from the Three Gorges project. That dam, audaciously immense, also required the relocation of rural and urban populations. Well before the project was complete, the government foresaw the forced migration of over 1.2 million people and the partial or total inundation of two cities, eleven countries, 140 towns, 326 townships and 1351 villagers, to create a bogglingly big reservoir – over 400 miles long. The reservoirs of such dams are breeding grounds for malaria mosquitoes and malaria prevalence in the regions ringing such reservoirs is far above the norm. The Chinese peasants who lived in the areas now flooded by Three Gorges‘ reservoirs were pushed onto marginal or unfarmable land, effectively marginalizing them from meaningful economic activity.

In Brazil, meanwhile, over one million people have been displaced by the development of hydroelectric dams, with many human rights violations along the way. The Brazilian group MAB – Movement of those Affected by Dams or barragens, in Portuguese – contends that Brazilian hydroelectric power is another sop to industrial concerns, while the peasantry and indigenous groupings pay through massive spatial dislocation. Other beneficiaries include Western turbine manufacturers and joint Brazilian-Western industrial and raw materials processing enterprises that can make good use of cheap energy – cheap, because the price per megawatt doesn’t account for the ecological and human cost. Meanwhile, the middle and lower-middle classes, teetering perpetually on the brink of destitution, pay elevated rates as compared to the transnational conglomerates gorging on cheap energy.

But this isn’t some sort of not-in-my-backyard complaint. The carbon produced by fossil-fuel combustion goes into all of our backyards and hard decisions must be made: what to power, what to power it with, what will produce the least CO2 per unit of power? The surprising upshot is that even after deploying such relentlessly pragmatic measuring tools, dam construction may not be much good. Scientists working in Brazil have found that dams with wide, shallow reservoirs – particularly those in tropical biomes – may submerge so much forested or vegetation-covered territory that they may be net greenhouse gas emitters.

For example, the Balbina hydropower project in tropical Amazonas, one of Brazil’s northernmost states, submerged more than 2,600 square kilometers of forest for a small output of „clean“ hydropower and a large output of greenhouse emissions. The emissions come not merely from the inevitable costs of building concrete and turbines and shipping in construction workers and construction materials, but also from the way the dam disrupts the ecology in which it sits.

When reservoirs build up behind gigantic shields of concrete, they flood and drown endless hectares of vegetation – trees, shrubs, savannahs, scrub. As the dead flora slowly rots, decomposing in the lower depths of pools of frigid reservoir water, it produces methane, which remains mostly stable, due to the way the water in the bottom reaches of the water is pressurized – although some still bubbles up to the surface. But when that methane-riddled water bursts through churning turbines, the methane dissolved in it shoots into the atmosphere, flooding it with a greenhouse gas significantly more potent than carbon dioxide. As Phillip Fearnside, the chief researcher focusing on tropical dams, especially in the Brazilian Amazon, comments, „The ultimate contribution of dams to carbon emissions is the difference between the carbon stock in the forest prior to flooding and that in the reservoir once the forest has decayed and an equilibrium is reached.“ That can be a lot.

Dam reservoirs are effectively a form of deforestation, except the flooded areas will not regrow until they are unflooded, as opposed to clear-cut forests, which can regrow if they don’t undergo desertification. Once we see tropical reservoir creation as necessarily entailing deforestation, Green hydropower seems more like the pat advertising slogan that it is than the accurate description of reality that its boosters hold it out to be.

And what about the Asian mega-dams reliant upon Himalayan headwaters or dams in areas with relatively low stocks of vegetation, which won’t be veritable methane factories when massive tracts of land are submerged? Ask the experts. Anthropologist Thayer Scudder of Caltech, a member of the World Commission on Dams and formerly a consultant to the World Bank on dam projects, comments, „Climate change is going to very adversely affect big dams. These dams are going to meet relatively short-term needs. What’s the situation going to be 30 to 50 years from now, which is when they think the glaciers may be gone?“

The leading East Asian environmental historian Kenneth Pomeranz adds that the Himalayas are young mountains, with lots of dirt. As a result, the water that descends from them into South and East Asian watersheds and Bhutanese, Indian, Chinese and Nepalese dams are loaded with tons of dirt. Dam reservoirs will quickly silt up, giving the massively expensive dams abbreviated life spans – while the even slight vegetative stocks will be permanently removed from the bio-carbon cycle and the never negligible costs, pecuniary and ecological, of building the dams themselves will remain sunk. The peasants ushered off their land in the name of cheap energy won’t be building submersibles for algae farming either. Their lives will be permanently disrupted, as they shift to barely arable land or become additional unwilling émigrés to what urban theorist Mike Davis calls a planet of slums. It is for that reason that Pomeranz comments, „At least in the long run, technologies such as wind and solar seem much better bets to provide genuinely clean and affordable power.“

So, why are dams getting built willy-nilly? One could argue that it’s endemic short-sightedness, an affliction to which state managers under capitalism are particularly prone. But that’d only be part of the story. The other part is institutionalized bribery or, in the technocratic argot of climate change negotiations, the CDM. Through this bit of legislative chicanery, first world countries purchase carbon credits from third world countries, in effect paying for „green“ infrastructure projects. In turn, the industrialized countries of the West can elect to postpone carbon reductions, since they’re already reducing carbon: just not in their economies, while third world countries get paid to develop clean energy sources so that they won’t dump even more greenhouse gases into an already overstuffed atmosphere. It’s all a bit of a stretch. At best: International Rivers Executive Director Patrick McCully argues, „This is a huge scam … Three-quarters of them are already built when they go for carbon credits. It’s hard to argue that they need the carbon credits to get built.“

So, can we get clean energy from moving water? Absolutely. Small dams might be built judiciously, while run-of-the-river dams, with turbines that don’t interrupt riverine flow, could also work well. And tidal dams might work, too, although they pose their own problems to marine life. But mega-dams? Not a chance.

Comments are closed.