MAKERS OF BENGALI LITERATURE : RAMPRASAD SEN

MAKERS OF BENGALI LITERATURE : RAMPRASAD SEN

ACADEMIC PAPER

“O my heart, you know not cultivation.

This human soil is lying fallow

and it would have produced gold if cultivated”

The Indian concept of culture (Kristi, samaskriti) is defined in the above three lines. “The sharpening of human sensitivities, feelings, emotions, and sensibilities through art is one of various ways by which man can ‘cultivate’ the soil of life to make it yield golden harvest in return”. Thus the poet Ramprasad Sen wrote about the main concept of Indian Culture as stated by Niharranjan Roy.

“No flattery could touch a nature so unapproachable in its simplicity. For in these writings we have perhaps alone in literature, the spectacle of a great poet, whose genius is spent in realizing the emotions of a child.Willam Blake, in our own poetry, strikes the note that is nearest his, and Blake is by no means his peer.

“Robert Burns in his splendid indifference to rank, and Whitman in his glorification of common things, have points of kinship with him. But to such radiant white heart of child-likeness, it would be impossible to find a perfect counterpart.”

– Sister Nivedita (Margaret Noble:1867-1911) on Ramprasad Sen

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sister_Nivedita

belurmath.org/kids_section/24-visit-to-niveditas-school

cwsv.belurmath.org/volume_5/questions_and_answers/in_answer_to_nivedita.htm

Ramprasad created a new form of poetry known as ‘Sakta Padabali’ in Bengali, and a new style of singing called ‘Prasadi’. After Ramprasad there was a remarkable outburst of Sakta poetry in Bengal.

His view of life was liberal. He was against racism, castism and untouchability, and generally opposed the Hindu orthodoxies of the conservative society.

Ramprasad believed that there should not be any religious conflict between various sects and cults, since God is one. He wrote, “One in five, five in one mind, should not go into conflicts.” ( ore eke panc, pance ea, non korna sweshasweshi)

Just as the message of Chatanyadeva was spread through his kirtan-singing and dance in the fifteenth century, Ramprasad’s message spread through his songs in the eighteenth century.

The Family

Ramprasad was born in a Baidya (caste of Ayurvedic doctors) familyof West Bengal. Ramprasad’s ancestor Raja Seiharsha Sen, the court physician of Sultan Fakurddin in the fourteenth century, had received the title of Raja from the Sultan.

The family tree:

Sriharsha – Bimal – binayak-Rosh – Narayan – Sangu or Sang – Sarani – Krittibas – Ratnakar – Nityananda – Jaggannath – Jadunandan – Ranjan – Rajiblochon – Jayakrishna – Rameswar – Ramram – Ramprasad.

Ramprasad made reference to his forefathers, especially Krittibas Sen and his father Ramram Sen. The family initially was staying in Dhalahandi in the district of Birbhum, then shifted to Kumarhatta-Halisahar (then in the district of Nadia). His father was a Sanskrit scholar, an Ayurvedician and a poet.

“Tadangaj Ramram mahakobi gunodham

Sada jara sadaya Abhaiya “

Ramprasad also mentioned the scholarly forefathers, who supported many charities.

The family lost their wealth; Ramprasad’s father did not fare well, and died early.

RAMPRASAD’S LIFE AND TIME:

“It is amazing

Others brag about their happiness

I brag about my sufferings” – Ramprasad

There is a debate between the scholars regarding the year of birth of Ramprasad; it varies from 1720 to 1723, however it is now widely agreed to be 1720. He learnt Sanskrit thoroughly, including some Ayurveda. He was not willing to be an Ayurvedis practitioner and started learing Persi. Persi was the state language of Bengal and jobs were available for those who were proficient in the language. He also learnt Hindi and Urdu. His knowledge of these three languages can be seen in Bidyasundar.

His birthplace, Kumarhatta, (also known as Halisahar) was situated on the eastern bank of the river Ganga, then in the district of Nadia, but now in the district of North 24 Parganas. Halisahar has a long tradition of Sanskrit learning and Vaishanavas. It is the birthplace of Iavar Puri, whom Chaitanyadeva respected as one of his religious models. Chaitanyadeva and his associates visited this place and it had become a place of pilgrimage. Sribas, an associate of Chatanyadeva, and Brindaban Das, poet of Chitanyabhagabat, stayed here in the sixteenth century. It also had a tradition of Sakta worship. Ramprasad got a piece of land around 1165 BS from Suvadra Devei of the Sabarna Raychoudhury family of Barisa, Kolkata, which was a place of worship place for earlier Sakta-Tantrics, including Ramkrishna Choudhury (around 1650). Ramprasad shifted to this place later and made his hut and continued his rituals on the platform where earlier Tantraic saints had performed rituals of their own.

Ramprasad took a job at Kolkata with landlord Durgacharan Mitra of Garanhata, Kolkata, due to the early death of his father and financial problems. He had an older half-brother Nidhiram (from the first marriage of his father) and a younger brother, Biswanth. One of his two sisters, Bhabani Debi, was married to Laxminarayana Das of Kolkata. Ramprasad respected her as a goddess, and called her ‘Laxmi’. He had two nephews, Jagganath and Kriparam, who were very close to him. His elder sister Ambica Devi was a widow.

Ramprasad got married to Yasoda Devi (also called Sarbani Devi), daughter of Loknth Dasgupta of Bhajanghat –Nadia. Ramprasad had two sons – Ramdulal and Rammohon, and two daughters – Parameswari and Jagadiswari.

Ramprasad used to write devotional poems in the books of accounts of his employer.

O mother! Give me your treasure-ship,

I am not ungrateful, O Sankari.

I cannot stand all and sundry

Looking at the treasure of your feet.

Forgetful Tripurari is your steward-

Shiva is pleased with a trifle and generous by nature,

Yet you keep your treasure under his charge.

Half the body is leased out,

But what a heavy salary for Shiva.

I am your servant without pay,

My only right is to the dust of your feet.

If you adopt your father’s way, then I stand defeated.

If, however, you adopt my father’s way,

Then I may attain you.

Says Prasad, I am undone with

The trouble of such a post,

But if I can get at those feet of yours,

I can easily get over my difficulties.

(Amai de ma tabildari)

– Translated by Swami Budhananda

The account-book poems were brought to the notice of the employer, who read them and understood the greatness of the poems. He told Ramprasad to leave the job and go back to his native village, and offered him a monthly allowance of 30 rupees.

Ramprasad came back to Halisahar and continued his poetic and religious activities, but had various problems:

„I spent my days in fun,

Now, time’s up and I’m out of a job.

I used to go here and there making money,

Had brothers, friends, wife and children

Who listened when I spoke . Now they scream at me

Just because I ‚m poor. Death’s

Fieldman is going to sit by my pillow

Waiting to grab my hair, and my friends

And relations will stack up the bier,

Fill the pitcher, ready my shroud and say

So long to the old boy

In his holy man’s get-up.

They’ll shout Hari a few times,

Dump me on the pile and walk off.

That’s it for old Ramprasad.

They’ll wipe off tears

And dig in to their support.“

– Ramprasad (Gelo din mitche rongo rosse)

Translated by: Leonard Nathan and Clinton Seely

His compositions were getting more popular every day, attracting kings, landlords, common men, beggers, farmers, boatmen. Krishnachandra Ray (b.1710 ), the Maharaja of Nadia, heard his songs and became an admirer of his work. He used to visit Halisahar, not very far from his capital Krishnanagar, in order to enjoy the songs of Ramprasad. The Maharaja offered him the post of the court poet which saint poet refused.But Ramprasad visited Krishnanagar and Murshidabad. There is a story that Nawab Sirajudaula, the ruler of Bengal, heard him singing and came to request a song. Ramprasad started with Hindusthani classical and Gazals but Siraj wanted to listen to the devotional Bengali songs. This story is quoted by Sister Nivedita and many others.

Bengal had some talented poets in the eighteenth century. Baratchandra Ray (b. 1712) was another prominent literary figure, and was the court poet of Maharaja Krishnachandra. The Maharaja was a patron of scholars and poets, having “Navaratna” [W2] in his court. Bharatchandra was famous for his “Annadamongal” which created a new style of Mangal Kabya. He also had written some shorter poems, but not like Ramprasad’s Sakta padabali[W3] .

Bharatchandra’s narration of the story of Vidya and Sundar (1753) is generally recognized as his greatest achievement . Simarly a version of Vidya-Sundar was written by Ramprasad .

Other important literary works of the eighteenth century include: Bhaktiratnakar (vicorously [W4] an encyclopedia of Vaishnav lore) by Narattom Chakraborty; Dharmamaongal by Ghanaram Chakraborty and Manikram Ganguly (1711 and 1741 respectively); Siva- Sankirtan or Sibayan by Raneswar Bhattacharyya; and Ramayana (1762) by Ramananda Yati. Other luminaries of the period include poet-composer Tappa singer of new style Ramnidhi Gupta famous as Nidhubabu ( b.1741) and Ksali Mirza (Kalidas Chattopadhay, 1750-1820) and many others.

[W5] The introduction of the printing press was soon destined to change the course of contemporary literary currents. The Bengali types were first used in Halhed’s Bengali grammar (in English) printed in 1778. (Sukumar Sen: 1979)

Ramprasad’s close friend Ramtanu Ganguli used to accompany Ramprasad’s singing with dhole (a local drum). Ramtanu was known as Tanudhulki. Bhajahari was Ramprasad’s associate and helper, who followed him everywhere. Balaram, known as Bala Fanchata, was famous for singing his Kalikirtan.

Ramprasad received land donations from some rich persons/landlords-

- From Krishnachandra Ray – 100 bighas

- From Subhadra Devi – 1 bigha

- From Darpanarayana Ray (Sabarna Raychoudhury family of Kolkata) – 2 bighas

- From Darpanarayana Ray, Sriram Ray and Kalicharan Ray – 8 bigha

After some time the monthly allowance of 30 rupees was stopped. Despite receiving the land donations, Ramprasad had financial problems. He was donating freely and became very famous for his hospitality. Many Kalikirtan group singers and admirers used to vist him. Initially he used to stay in a hut but later made a small building (Kothabari).

Once he travelled from Kasi (Varanasi) but came back from Trebeni as per the instruction of Mother Kali. But it is said that later on he had visited Kasi.

He used to visit the following friends and admirers:

1. Raychoudhury family of Barisa, Kolkata (he used to sing in their Kali temple)

2. Ghosal familu of Bhukailash, Kidderpore, Kolkatqa

3. Churamani Dutta – North Kolkata

4. Gokul Mitra – North Kolkata

5. Nabakrishna Deb – Sovabazar, North Kolkata

6. Maharaja Nandakumar – Murshidabad and Birbhum

7. Baishnabcharan Sett – North Kolkata

It is said that Madhabacharyya, his first Guru from their traditional Kulaguru family, taught him Sakta and Tantric rituals. There is also mention of another name: Kripanth is there in one of Ramprasad’s poems, but researchers are not sure whether it is the name of the Guru or some religious code. Later on Agambagish, the famous Tantric, taught him Tantra.

As a matter of fact, this Guru-vada may be regarded as the special characteristic, not for any particular sect or line of Indian religion, but of Indian religion as a whole. (Shasibhusan Dasgupta)

Ramprasad, though Sakta of Tantric Cult[W6] , was against animal sacrifice. It was mentioned in his poetry. Also there is a debate whether he was a Nirakara (formless or shapeless) or Sakara (with form or shape) worshipper.”Tara amar nirakara” (my Tara is formless) is mentioned in the following poem:

Oh, this is a hundred times as true as the Vedas –

My mother is formless.

What then is the use of your making

Images of metal, stone or clay?

Making an image out of the stuff of your mind

Install it on the lotus seat of your heart.

– Translated by Swami Budhananda

In another poem he says:

O Mind, do you still cherish this fantasy of yours?

What is Kali that you stare and haven’t seen her?

O, you know the Three Worlds are Mother’s image,

You know, but do you really believe it?

What kind of thing is your heart that it makes Her likeness

in clay and then

offers it up prayers?

– Translated by Leonard Nathan and Clinton Seely

But Ramprasad also gave an account of Sakta worship. There is no evidence that he made a temple with an idol for worship; only a blank platform could be seen at his place of worship. But to attract common people he used to worship an idol of mother Kali. Ramprasad scorned caste, ritual, idol worship, pilgrimage and animal sacrifice; for him all of these were externals in which he found no no religious content.

One Rajkisore inspired him to write “Kalikairtan” –“Srirajkisoreadeshe Srikobiranjan roche gan moho andher ousad anjan”.

This may be Rajkisore Mukherjje, a relative of Krishnachandra, or Rajkisore Ray (Dewan of Hoogly); both were well-known persons at that time.

Krishnachandra gave him the title “Kabiranjan”, or another view is that someone from the Sabarna Raychoudhury family of Barisa might have given him the title.

WAR, FAMINE, SANYASI REVOLT

During the lifetime of Ramprasad there were attacks, looting, and torture of the Bargis (Maratha) from 1742. Common people were helplessly tortured and killed in some areas of West Bengal, while many people escaped to safer places. A peace treaty was signed with Marathas paying heavy compensation. But Nawab’s rule was not peaceful.Decoacy[W7] was a common factor, and there was again forceful torture by the ruling class for the purpose of tax collection.

The East India Company was gathering strength, spreading their business and power. After their initial defeat at the hands of Siraj they reached an understanding with some prominent Hindu landlords and Muslim associates of Nawab. Sirajudaulla was defeated in the battle of Plassey in 1757 and brutally killed. Under the banner of the East India Company, the British were granted defacto power, but war continued.

The great famine of 1769-70 had caused shortages of food everywhere and about one third of the population of Bengal died. Ramprasad had witnessed all of this. “Anno de, anno de ma, anno de” (“give food, give food, mother”) – that was his cry.

In one of his poems, Lord John Teignmouth wrote:

Still fresh in memory’s eye the scene I view,

The shrivelled limbs, sunk eyes, and lifeless hue;

Still hear the mothers’ shrieks and infants’ moans,

Cries of despair and agonizing moans,

In wild confusion dead and dying lie;

Hark to the Jackal’s yell and vulture’s cry,

The dog’s fell howl, as, midst the glare of day,

They riot unmolested on their prey!

Dire scenes of horror, which no pen can trace,

Nor rolling years from memory’s page efface

– Memoirs of the life and correspondence of Lord John Teignmouth Vol.1, pp25-28, London, 1843

There was a Sanyasi revolt in 1772-73, and political unrest continued throughout the life of Ramprasad. Bamkimchandra Chattopadhyaya had skillfully documented the famine and Sanyasi revolt in his famous novel Anandamath. Ramprasad’s feelings can be understood through his poems, where he reflects the condition of people: their suffering, the demand for food, large-scale poverty and war. He had become the voice of Bengal.

“Does suffering scare me? O mother,

Let me suffer in the world. Do I require more?

Suffering runs ahead of me and runs after me.

I carry it on my head and set up a stand

In the bazaar to peddle it.

I’m a poison worm, I thrive on poison;

I carry it wherever I go.

Prasad says: Mother, lift off my load.

I need a little rest. It’s amazing!

Others brag about their happiness,

I brag about my suffering.”

– Ramprasad

Ramprasad became a legend and myths were spread regarding his achievements. It is said that he performed some Tantric rituals at the time of famine and prevented an epedimic. It was also believed that he possessed certain mystical powers which had once made the idol of Chetreswari of Chitpur turn to hear him singing.

There were theoritical conflicts between the Vaishnavas and Saktas of Bengal.

One Vaishnava poet, Aju Goswai, used to make parodies out of Ramprasad’s poems and songs. Sometimes they had face-to-face debates in the form of songs, while a crowd looked on. Some examples of Aju Goswai’s performance are of great interest. One of Ramprasad’s most inspiring songs was:

“Taking the name of Kali, drive deep down, O mind,

Into the heart’s fathomless depths,

Where many a precious gem lies hid…”

Aju came out with a rejoinder:

Drive not, O mind, very often,

For your breath will get choked in no time.

You, phlegmatic type,

Should not do excess driving.

If you contact fever, mind,

You will have to go to the abode of death.

Too much greed brings one to grief;

Why labour in vain?

Just go floating and catch the boat

Of the feet of Shyma or Shyam.

(dubisne mon ghori ghori)

Ramprasad sang:

Come, let us go for a walk, O mind,

to Kali, the Wish-fulfilling Tree,

And there benefit,

Gather the four fruits of life ….

(Ay mon barate jabi)

Aju’s reply:

Why, O mind, should you go for a walk?

Don’t you be induced by anyone to go anywhere…

Maybe going to the Wish-fulfilling Tree,

You will pick a wrong fruit in place of the right one.

(keno mon barte jabi)

If Ramprasad sang:

“The world is mere framework of illusion”

(e songsar dhokar tati)

Aju flashed:

This very world is a mansion of mirth;

Here I can eat, here drink and make merry…

(e songsar rasser kuti)

– Translated by Swami Budhananda

It will thus be seen that though Aju behaved mostly like a clown and excelled in parodying Ramprasad, he was not without some spiritual perspective.

A contemporary of Ramprasad named Balaram Tarkabhusan, who was also from Halisahar, and was a Sanskrit scholar and Naiyakik (school of Indian philosophical logic), used to taunt him and call him a drunkard. The day before his death, Ramprasad met him and replied with a song:

“rasane Kali nam rot re ….

Kali jar hride jage, torko tar kotha lage

A kebol badartha matro khunjetechi ghot pot re”

(In whose heart Kali is awake arguments do not touch him)

Around 1781 Ramprasad felt his earthly life was coming to an end. He walked into the river Ganges with the clay idol of Kali on the immersion day of Kalipuja (the same day Diwali is celebrated), composing and singing 4 songs. He sang the last words of the song then said “it is achieved”, and died a mystic death in the river.

The last 4 songs:

1. Wait a minute, O death (tilek dara ore saman)

2. Tell me, brother, what happens to one after death (bol dekhi bhai kl hoi mole)

3. My life is spent in vain (morlam bhuter beggar khete)

4. “Tara, do you remember me any more?

Mother I have lived happy, is there happiness hereafter?

Had there been any other place, I could not have

besought you. But now, Mother, having given me hope,

you have cut my bonds, you have lifted me to the tree’s top.

Ramprasad says: My mind is firm, and my all is

finished. I have offered my gift.”

– Translated by Thompson.

In 1923 Thompson described how he had heard Ramprasad’s songs sung by “coolies on the road, or workers in the paddy field, by broad rivers at sunset, when parrots were flying to roost and the village folk thronging from marketing to ferry … The peasents and pundits enjoy his songs equally. They draw solace from them in the hour of despair and even at the moment of death. The dying man brought to the banks of the Ganges asks his companions to sing Ramprasadi songs“.

Similar observatons were made by poet-editor Isvarchandra Gupta (b.1812) 176 years ago. Isvarchandra was the first poet-editor to print and write about Ramprasad in 1833. Thereafter DayalChandra Ghosh, Atul Mukherjee, Kaliprassan Kavyabisarad, Ramgati Nayaratna, Tinkari Mukherjee, Jogeshchandra Gupta et al carried on this work. Scholars and researchers have discovered additional information from various sources.

GODDESS KALI

Ramprasad [W9] goddess Kali. India has a long tradition of Mother Goddesses from ancient times onwards in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions. In eastern India the Tantric cult spread in Assam and Bengal. The Buddhist mother goddess Tara was assimilated into the Hindu Sakta cult. Kali, Tara and Shyama are all pseudonyms of Goddess Kali. These three names of Mother Kali were all frequently used by Ramprasad.

Background of Kali

Kali, one of the most intoxicating personifications of primal energy in the cosmic drama, gained an extraordinary popularity in Saktism and is the object of fervent devotions in tantric forms of worship. She is a power-symbol embodying the unity of the transcendal. As we have seen[W10] , she had made her official debut [W11] c. AD 400 in Devi Mahatmya, where she is said to have emanated from the brow of Durga during one of the battles between the divine and anti-divine forces. In this context Kali is considered the forceful form of the Great Goddess Durga.

The name of Kali has been used generically from antiquity. It has been common practice in India to attribute the achievements of one goddess to another. The idea is that the different manifestations are for a certain definite purpose, and in reality there is one Devi who assumes various forms to fulfill various purposes. Sometimes she assumes a frightening form and sometimes a benevolent form.

Her garland of fifty human heads, each representing one of the fifty letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, symbolizes the repository of knowledge and wisdom, and also represents the fifty fundamental vibrations in the universe. She wears a girdle of human hands; hands are the principal instruments of work and so signify the action of karma or accumulated deeds, constantly reminding us that ultimate freedom is to be attained as the fruit of karmic action. Her three eyes indicate the past, present and future. Her white teeth, symbolic of satta, the translucent stuff of intelligence, hold back her lolling tongue, which is red, representing rajas , the activating quality of nature leading downwards to tamas (inertia). Kali has four hands (or, occasionally, two, six or eight). One left hand holds a servered head, indicating the annihilation of ego-bound evil force, and the other carries the sword of physical extermination with which she cuts the thread of bondage. One right hand gestures to dispel fear and the other exhorts to spiritual strength. In this form she is changeless, limitless primodial power, acting in the great drama, awakening the unmanifest Siva beneth her feet.

– Ajit Mookerjee; Kali the Feminine Force.

There is reference to Kali from Krittibas Ramayana in a Bengali work of the fifteenth century “asitbarana Kali kole Dasanan” (Dark colour Kali with Ravana in her lap)

Also in the texts of Chandimaongal and Manasmongol, the Mother goddess is present under various names.

Ramprasad’s Kali:

“Who is there that can understand what Mother Kali is?

Even the six darshans are powerless to reveal Her.

It is She, the scriptures say, that is the Inner self

Of the yogi, who in Self discovers all his joys:

She, that Her own sweet will, inhabits every living thing.

The macrocosm and microcosm rest in Mother’s womb;

Now, do you see how vast it is?

In Muladhara the yogi meditates in Her,

And in the Sahasrara:

Who but Shiva has beheld Her as She really is?

Within the lotus wilderness She sports beside Her mate, the Swan.

When man aspires to understand Her Ramprasad must smile;

To think of knowing Her, he says, is quite as laughable

As to imagine one can swim across the boundless sea.

But while my mind has understood, alas! My heart has not;

Though but a dwarf, it still would strive to make a captive of the moon.”

– Ramprasad (Translated by Swami Budhananda)

TANTRA

Ramprasad’s worship of Kali was related to Tantra, and the code of tantric practices were there in his work. The tantras offer unique discipline to wake up the finer dynamism of spirit. It moves the vital and the spiritual energies and transforms the vital nature by spiritual infusion. But the transformation is gradual, the blind seeking of the vital nature including visual obscurities is slowly eliminated, not by the suppression but by exposing the nature and constitution of vital being. (Dr. Mahendranath Sircar)

There is a view that tantric texts are wrriten with Buddhist influence. But it clear that the development of Tantra made by the Buddhists and the extraordinary plastic art they developed, did not fail to create an impression on the minds of the Hindus, and they readily incorporated many ideas, doctrines and gods originally conceived by the Buddhists in their religion and literature … The bulk of literature which goes by the name of Hindu Tantras arose almost immediately after the Buddhist ideas had established themselves. (Binaytosh Bhattacharyya, Introduction to Sadhanmala vol. II )

However, scholors have discussed the existence of a pre- and post-Vedic culture of Tantra.

Even in Hindu culture there are different variations of Tantra. Ramprasad practised a softer and more human version of Tantra, most probably based on kularnavtantra: “Even among the Saktas there have been those against bloodshed, and those who have tried to spiritualise the texts on which it is based. The best the Tantras have always insisted that externals worship of no avail.[W12] ” If the mere rubbing of the body with mud and ashes gains liberation, then the village dogs who roll in them have attained it, says the Kularnava Tantra, which is as least as old as the thirteenth century. (Earnest A. Payne, Sakta)

“What is the use of making dolls out of metal, stone and earth?

Don’t you know, O fool, that the whole universe is the image of the Mother?

You have brought a handful of gram, O shameless one, as an offering to the Mother – to Her who feeds the whole world with delicious food.

What use, O foolish mind, in making illuminations with lanterns, candels and lamps?

Let the mind’s light grow, and dispel its own darkness, day and night.

You have brought innocent goats for sacrifice.

Why not say, “Victory to Kali!” and sacrifice your passions, which are your real enemies?

Why those sounds of drum? Only keep your mind at her feet and say –

“Let thy will, O Kali, be fulfilled, and saying to clap your hands.”

– Ramprasad, translated by Dineshchandra Sen

Ramkrishnadeva (1838-1884), another important figure of Indian religious thought, often spoke about Ramprasad singing his songs, and was a follower of the same Tantric cult followed by Ramprasad.

Ramprasad as part of the Indian Bhakti cult

In a point of time [W13] some of the saint-poets of upper, central and northan India flourished earlier than the Bauls of Bengal, and many of them were contemporary with, if not earlier than the Vaisnava-Sahajiya of Bengal. When, therefore, we speak of the Sahajiya background of these non-Bengali medieval poets, we mean the Buddhist Sahajiya movement in particular. A study of the poems of these medieval poets, particularly of the poems of Kabir, decidedly the most prominent figure of the middle age, will reveal that there is a clear line of continuity from the Buddhist Sahajiya poets to medieval poets. But the difference between the earlier school and medieval schools lies in the element of love and devotion, which is conspicuous by its absence in the Buddhist Sahajiya school… But in spite of this difference, general similarity in spirit, in literary form and sometimes even in language, is indeed striking. (Shasibhusan Dasgupta, Obscure Religious Cults)

Ramprasad was aware of this Bhakti cult and was a part of a Bhakti cult himself, adding Sakta non-orthodox Bhaktism to it. Many common words and codes[W14] originated from Charyapada: the Buddhist Sahjiya poems in the old Bengali language influenced Kabir, Dadu and many other Bhata poets of the Hindi language. This influence continued to the Vaisnava-Sahajiyas like Chandidas and other Sahajiyas of Bengal, then to Sufi Fakirs like Llan Fakir and Pagal Kanai. All of these influences can be seen in Ramprasad.

Kabir says that roaming about on pilgrimage and bathing in the sacred rivers are absolutely futile so long as the mind is not purified through sincere love of the lord. Ramprasad wrote:

“What have I to do with Kasi? The Lotus-feet of

Kali are place of pilgrimage enough for me.

Deep in my heart’s lily meditating on them, I

Float in an ocean of bliss. In Kali’s name,

Where is there place for sin? When the head is not,

Headache cannot remain. As when fire consumes a

Pile of cotton, so all goes, in Kali’s name.

The worshipper of Kali laughs at the name

Of Gaya, and at ancestral offerings there, and the

Story of salvation by ancestor’s merits. Certainly

Siva has said that if a man dies at Kasi he gains

Salvation. But devotion is the root of everything, and salvation

but her handmaid who follows her.

What is the worth of salvation if it means

Absorption, the mixing of water with water? I love

To eat sugar, but I have no wish to become sugar.

Prasad says joyously: By the power of grace

And mercy, if we think on the Wild-Locked

Goddess, the Four Goods become bad ones.”

(Translated by Edward Thompson)

The lotus is another common metaphor and symbol, from Buddhist Sahajiyas to medieval Saint poets, Mother cult Mongal kavyas of Bengal, Traditional Vaishnavas and Sahajiya Vhaisnavas, Fakirs and Bauls.Ramprasad used it frequently in “Kamal”, ”Padma”, etc.

A study of Kabir and Ramprasad’s poems will reveal that they had a yogic system of their own involving the theory of lotus or plexus, the nervous system and the control of vital wind. “[W16] We find the two important nerves in the left and the right, most commonly known as the Ida and Pingala, as the moon and the sun, or the Ganga and Jamuna. The meeting place of the three nerves Ida, Pingala and Susumna is, as usual, described here as Tri-veni (i.e. the meeting of the three courses).

Ramprasad wrote:

Tirhe gaman ,mithya bromom mon

Utaton korona re

O mom Tribeni ghate boiso

Sital hobe ontopure

(Do not keep your mind bothered by visiting holy places, sit on the bank of Triveni, your heart will cool down)

After some time Lalan Fakir wrote:

Tripiner tir dhore sei khani Sai chole phere

Uporupor berao ghure se govir jole dekhbena

(Sai moves around the bank of Triveni

You are moving only from the outside, not gone into depth.)

These coded words are frequently seen in Kabir and other Saint poets, Ramprasad and later in Sakta and Vaishnava, Baul and Fakirs – a continuous Indian Tradition.

“Indian literature grew not only under some common religious movements but they show striking similarity even in form, technique and knowledge. The enigmas of Charya songs of Kabir and Sudar-das are substantially of the same nature as are found in the rural areas of Bengal of which Ramprasad was a part.” The sandha-bhasa thus becomes an all-Indian literary technique; forgiving expression to esoteric doctrines, it has an unbroken history for centuries. (Shasibhusan Dasgupta)

POEMS AND SONGS

Ramprasad’s poems came spontaneously from the soul. Their outward simplicity reflected the voice of rural people, reached common people and spread throughout Bengal. His poems are based on the expression of day to day life and human suffering. Metaphors of land, agriculture, water, trees and the body are frequently seen.

“Tarar jomi amar deho, ithe ki ar apad atche

O je deber deb, sukisan hoea mahamantra beej buneche”

(My body is Tara’s land, what could be a danger in it,

That is God’s God, being a good farmer.)

He used very little ornamental language in his padabali (shorter poems).

“Mind, you do not know how to farm.

Your fields remain untilled; had you but sown,

A golden harvest had[W17] waved. Now make

Kali’s name a fence, that the crops may not be

Destroyed. Not Death himself (O my mind!)

Dares come near this fence, your long-haired

Fortress. Today or after a hundred centuries –

You know not when forfeiture will come.

To your hand is the present time, Mind

(O my mind!). Hasten to make harvest!

Scatter now the seed your teachers gave you, and

Sprinkle it with the water of love.

And if alone (O my mind!) you cannot

Do this, then take Ramprasad with you.

(Ramprasad, mon re krisi kaj janona, translated by Thompson.)

Leonard Nathan and Clinton Seely pointed out, “In fact, [Ramprasad] shares two decisive qualities with our contemporary poets: an intense feeling for the desperateness of the human condition, and a conviction that the poet’s personality is the proper subject matter of his poems.” (1982)

“[W18] The most interesting bulk of devotional songs relates to the worship of divinity under the special image of Sakti, although there are several songs which relate to other religious songs. Its origin must be traced to the recrusescene[W19] and ultimate domination of the Sakti cult and Sakti form of literature in the 18th century, which in its turn traced its origin in general to the earlier Tantric form of worship. Ramprasad, the greatest exponent of this kind of songs-writing of this period, began his career as the author of Bidya-sundar; but even through the erotic atmosphere of this half-secular narrative poem, the devotional fervour of the Sakta-worshipper expresses itself. But when Ramprasad late on realised the superiority of his ecstatic religious effusions as something more congenial to the trend of his life and genius, and burst forth even in the pages of his more studied and literary poems, the literary world began to be flooded with the tuneful melodies of religious ecstasy as a reaction from the comparatively arid thralldom of conventional verse.

The conflict between the Sakta and Baisanab sects obtains Bengali literature from time immemorial. As on the one hand Baisnab poets, steeped in the speculative, mystic and emotional realizations of the Srimad-Bhavat, were giving a poetic shape to their religious longings in terms of human passion and emotion and figuring forth the divinity as the ideal of love, the Saktas, on the other hand, were singing the praise and describing the glory of Adya Sakti through their Chandimangal poems. Regarded as literary ventures, those longer and more studied efforts of the Sakta writers, no doubt, hold a conspicuous place in ancient Bengali literature, but the Saktas could not attain the lyric predominance and passionate enthusiasm of Baisnab song-writers. There is a better space for losing oneself in poetic rapture in dealing with batsalya, sakhya, dasya, madhuurya and other familiar and daily felt emotional states than describing in a sober narrative form the feats and glories of the particular deity under the image of the Mother; but no votary of the cult before Ramprasad realized the exceedingly poetic possibilities of this form of adoration. In Ramprasad this new form of adoration of Supreme Being under the image of the Mother – a form naturally congenial to the Bengali temperament – finds its new characteristic expression. The image of divine motherhood, to Ramprasad is not a mere abstract symbol of divine grace or divine chastisement, but it becomes the means as well as the end of definite spiritual realization. Rising to the radiant white-heat of childlikeness, the poet realizes the emotions of the child and the emotions of a devotee.” (S.K.DE [W20] )

A Balyaleela poem:

Giribala, I can no longer try to quit Uma. In angry pride she sobs and sobs and will not have the breast. She does not want the chotted milk; butter or cream she will not eat.

The night has almost gone, and in the sky the moon has risen. Uma cries: Bring for me.

No longer (I say) can I try to quit Uma. Her eyes are swollen with her sobbing, all tear-stained in her face. Can I, her mother, bear to to see her so?

Come mother, come!” she says, and takes my hand; yet words she flung her ornament at me.

Giribala left his bed and sat him down, and tenderly took Gauri in his arms. Happy at heart and laughing as he spoke, ‘See, little mother, here’s a moon for you,” he said, and handed her a mirror. Great was her joy, as in the mirror she beheld her face, then countless moons more beautiful.

Ramprasad says Blessed indeed the[W21] within whose house Earth’s Mother dwells.

Uma’s mother speaks.

(Ramprasad, translated by Thompson)

Ramprasad is also the originator of “Pratibatsalya Rasa” (child’s love for the mother) in poetry.

All previous saintly poem-songs contained “Batsalya Rasa” (mother’s love for the child).

Sister Nivedita wrote: “But a great burden of his verses is the Mother. And in calling upon Her he becomes the ideal child. It is curious to reflect how a century and a half ago, almost before the birth of childhood into European art, a great Indian singer and saint should have been deep in observation of the little ones – studing them, and sharing every feeling, almost without knowing it himself. Once, indeed , he seems to justify himself:

“Whom else should I cry to, Mother?

The baby cries for his mother alone –

And I am not the son of such

That I should call any woman my mother!

Tho’ the mother beat him,

The child cries ‘Mother, Oh Mother!’

And clings still tighter to her garment.

True I cannot see Thee,

Yet am I not a lost child!

I still cry ’Mother, mother!’”

(Ramprasad, translated by Sister Nivedita)

Ramprasad, a confirmed Sakta poet, was considerably influenced by Baisnab ideas in his Kali-Kirtan and Krisna-Kirtan. Not only does he imitate in places the characteristic diction and imagery of Baisnab Padabalies, but he deliberately describes the gosthas, ras, Milan of Bhagabati [W22] following the text of Brindabanlila of Srikrisna. It does not concern us here whether the girl Parbati figures in a better artistic light with a benu and pachanbdai[W23] in her hand or whether the picture deserves the sarcastic comments of Aju Goswami… what we need note is that here as well as in his Agamani songs, Ramprasad is unmistakably utilizing Baisnab ideas. There is no distinction in reality, says Ramprasad in many a song, between Vishnu and Sakti, between Kali and Krisna.( S.K.DE)

“I love that Dark beauty,

With the ruffled hair, enticing the world.

So I love her.

This black darling resides in the heart

Of Mahadev [Siva], the god of all gods.

Again Krishna the Dark

Is very life of Brajaland [Vrindavan],

Engrossed with cowgirls there

Hence I love black. I adore it.

Banamali Krishna became the Black Goddess, Kali

So says Prasad [Ramprasad], making no distinction

Between the two.

So I love the dark beauty

Syama, the heart’s throb, the ruffled hair,

I love and adore her.

(Ramprasad, translated by Thompson)

This is the liberal view of Ramprasad finding one god the supreme in various names and images.

The songs of Ramprasad still reign supreme in our villages. In pastoral meadows, amidst sweet scents of herbs and flowers, with the gentle murmurs of the river flowing by, or in rice-fields where sounds of the cutting of grass or reaping of harvest lend a charm to the tranquil village-scene, one may often hear the Malasri songs of Ramprasad, sung by the rustics in the following strain:

“The brief day will pass, sure it is, O Mother Kali – and all the world will find fault with you that you could not save a sinner like me”.

(Nitanto jabe, kebol ghoshona robe go/Tara name asonkho kalonko robe go//)

(Translated by Dineshcahndra Sen)

War Poems

Ramprasad also wrote some poems on war. His experience of seeing the evils of war can be seen in these poems. These war poems are also something new to Bengali poetry. Isvarchandra discussed 9 such poems; what follows are selections from the original Bengali –

1.Ma koto natcho go rone (Mother how much you dance in war)

2.Joginigan sakal bhairab samara kore dhore tal

tat a thei thei drimiki / drimiki dha dha dampho badya rasal.

3.Ebama mar mar , mar mar robe dhai

4. ghono ghor ninadini ,samara badini , madanunmadini bes.

Only 3 written texts of Ramprasad are available; none of which are originals, but later copies. Details of these are listed below:

Vidaya-Sudar: Following the traditional narrative of Vidya and Sunsar, Ramprasad wrote Vidyasundar around 1759 with a request from his patron Krishnachandra. This is totally diffeent from his padabali style; the language is stiff. He had mixed Persian, Hindi and Urdu with Bengali and his knowledge of Persian and Hindi literature and language could be observed. The text was according to the popular taste of the time and some part of it was considered vulgur by the 19th century sense of morality. This was the longest poetic text of Ramprasad.

Kali-Kirtan: The first assimilation of two opposite schools of Hinduism, Vaihnavism and Saktaism, can be seen in this longer poem written in Panchali form. Ramprasad had taken the ideas of Krishnaleela and other Vaishnavsa images and superimposed them on the Mother Kali. Some part of it is highly Sanskritised and mixed with brajabuli. However it was very popular and sung by various groups until the middle of the 20th century. Kali’s rashleela etc were painted by early Bengal school painters in the early 19th century.

Krishna-Kirtan: This incomplete text was discovered in the line of the contemporary Vaishnava school.

Then two other poems were located:

‘Sitar-Bilap’

‘Agamani’

In total about 321 shorter poems or Padabalis are available now. All the poems have been collected from the memory of the people, people who had written them down during the lifetime of Ramprasad or afterwards, and preserved them.

SONGS

Ramprasad brought a new style of music which is known as “Pradsadi”, and has become extremely popular among the masses: among boatmen, weavers, farmers and also among the upper classes. He had studied Hindusthani Classical, Kirtans of the Vaishnavas style and he also heard Bauls – Vhaisnava Sahajiyas singing.

He has combined Bengal’s Padabali Kitran with Baul tunes – it is this invention that made him immortal in the world of Bengali songs.

INFLUENCE

Kmalakanta Bhattacharyya (1772-1821) was another important poet after Ramprasad. Others to mention are Maharaja Ramkrishna of Natore, Dewan Raghunath Ray (b.1750) and Ramdulal Nandi of Tripura (b.1785), but there are many others.

The semi-secular poems of Ramprasad attracted poets and composers from other religions. Antiny, a Christian of Portugese origin, and Sayed Jafar, a Muslim, wrote some songs on Kali in the early 19th century inspired by Ramprasad. Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976) wrote some excellent songs on Kali.

Ramprasad’s influence spread all over Bengal. There were other Ramprasads in East Bengal and Kolkkata who followed Ramprasad. Ramprasad’s poems were adapted into regional dialects. In some cases it was difficult to identify some shorter poems of Ramprasad’s as Dijwa or Diana Ramprasad was used in the Bhanita. Actually Ramprasad’s poems spread all over Bengal and won the hearts of the Bengali people.

Ramprasad became the folk poet of Bengal. His influence can be observed among the Kaviwaals of the 19th century, Bauls and Fakirs like Lalan Fakir (1774-1890) or Pagal Kanai who come from different socio-religious backgrounds.

Rabindranath Tagore used Prasadi tunes in at least 4 songs. Novelist Kamalkumar Majumder drawn our attention by reffering Ramprasad again and again. Ramprasad’s poems are intertextually used by some younger poets from 1970 and afterwards.

Novelist Subrata Mukhopadhyay has written a novel in 2009 based on Ramprasad’s life.

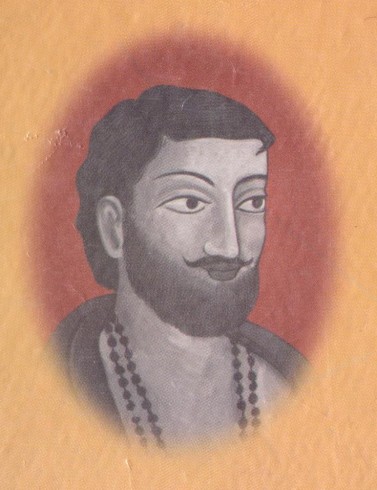

Within few years of his death a local folk painter Vona Patua painted his portrait, also showing his wife in the painting. Around 1792-93 A.W.Devis, a British painter, painted a portrait in oil which is preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Hundreds of Kali images were painted by the oil painters of the early Bengal school and the patuas of Kalighat in the early nineteenth century, inspired by Ramprasad. Painter Nirode Majumder did some drawings and oil paintings on Ramprasad’s themes between 1960- 1975.

Ramprasad was termed as “Best poet of Bengal” by Iswarchandra Gupra as early as 1854, “Viswa Kabi” by Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das for his universal appeal and “National Poet” by Edward Thompson in his book “Bengali Religious Lyrics-Sakta” (1923).

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramprasad_Sen

Many thanks for your facebook msg & the poem of Hesse. It is a great pleasure to be afriend of you.I have read German literature mostly in English & Bengali translation. Even one of my poems translated into German an published in an anthology gteom Germany as early as 1972-73.

Now I am working on Rabindranath Tagore’s paintin with special reference to Bauhaus .German painters from early 20 th century got interested abt Indian art & used materials from Indian literature ,spirituality acctracted them. Bauhaus group artists have studied Indian art and literature .Krtichner was the fist who copied Ajanta Murals ,also inspired by Ajanta murals of 6 th century he painted “five bathers”. Franz Marc used Buddhist Jataka elements. Paul Klee painted The Wild Man” (1922) see the image of Narasimha & other paintings,one clerarly based on Kalidas’s Sanskrit classical epic “Sakuntala”

KANDINSKY ALSO TALKED ABOUT iNDIAN SOUCES .

Supprisingly Tagore’s thoughts on painting have some similarity with the Bauhaus group -whith reading each other theories .

The cult og Kali and Bengali poet Ramprasad Sen(1720-1781) I am not very strong to write in English ,but you are aware of the the cult of Kali ,my draft paper on the poet Ramprasad Sen who wrote absolute new type of poems Shakta Padabali, attached two versions of the Ramprasad document ,corrected by Australian poet Stu Hatton .Ramprasad Has been translated by English writers from U.K. & America, France & Italian ,as far my knowledge not been translated into Getman.

[W1]Would it perhaps be better to use footnotes or endnotes for referencing quotations from other sources?

[W2]This word should probably be defined / glossed for non-Indian readers.

[W3]Is this the title of a poem, or a form made famous by Ramprasad?

[W4]I don’t recognise this word?

[W5]I’m not sure how this sentence relates to the previous sentence? Does this sentence list authors and works, or just authors?

[W6]This needs rephrasing? I’m not quite sure what you mean.

[W7]I’m not familiar with this word.

[W8]There’s a major leap between these two paragraphs.

[W9]worshipped the?

[W10]Where have we seen this? It seems you’re referring to text which is not actually in this paper?

[W11]‘official debut’ doesn’t seem like an appropriate phrase for a goddess.

[W12]This needs rephrasing, but it is a direct quotation.

[W13]I’m not sure what you mean by ‘In a point of time’?

[W14]I’m not sure whether this is the right word in this context?

[W15]This paragraph is confusing. There are many names I’m not familiar with, and I’m not sure I’ve got the meaning right after my editing.

[W16]Is this a quote? There is no quotation mark at the end?

[W17]would have?

[W18]Is this entire (long) paragraph a quote?

[W19]recurrence?

[W20]Is this the correct name of the source?

[W21]are those?

[W23]I’d suggest a translation of these words is needed.

Comments are closed.