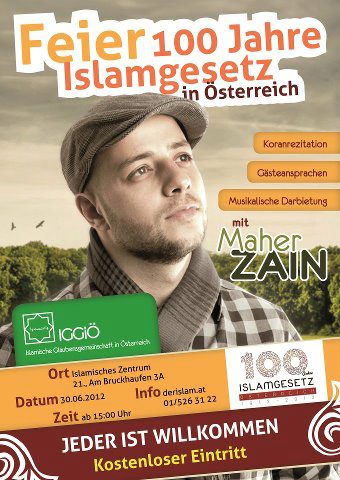

100jähriges Jubläum im Islamischem Zentrum 30. Juni 2012

http://www.derislam.at

Volksfest anläßlich des Jubiläums im islamischen Zentrum

Wo: Islamisches Zentrum Wien, Wann: 30.Juni.2012

Islam is a monotheistic and Abrahamic religion articulated by the Qur’an, a text considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God (Arabic: الله AllÄ�h), and by the teachings and normative example (called the Sunnah and composed of Hadith) of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim.

Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable and the purpose of existence is to love and serve God. Muslims also believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed at many times and places before, including through Abraham, Moses and Jesus, whom they consider prophets.

Austria is unique among Western European countries insofar as it has granted Muslims the status of a recognized religious community. This dates back to the times following the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878. Austria has regulated the religious freedoms (self-determination) of the Muslim community with the so called „Anerkennungsgesetz“ („Act of Recognition“). This law was reactivated in 1979 when the Community of Muslim believers in Austria (Islamische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Österreich) was founded. This organization is entitled to give lessons of religious education in state schools. It is also allowed to collect „church tax“ but so far it has not exercised this privilege and does not build, finance or administer mosques in Austria.

Parallel structures exist within the Islamic religious group. The religious life takes place in mosques belonging to organisations that represent one of the currents of Turkish, Bosnian and Arab Muslims. Among the Turkish organisations the „Federation of Turkish-Islamic Associations“ is controlled by the Directorate for Religious Affairs, whereas the other groups, such as the SüleymancÄ�s and Milli Görüş, may be considered as branches of the pan-European organisation centered in Germany.

Mit einem Festakt im Wiener Rathaus am 29. Juni 2012 feiert die Islamische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Österreich (IGGiÖ) 100 Jahre offizielle staatliche Anerkennung des Islams. Am Tag zuvor steht das Islamgesetz im Zentrum einer rechtswissenschaftlichen Tagung an der Universität Wien. http://juridicum.univie.ac.at/index.php

Das Verhältnis zwischen dem christlich geprägten Europa und dem Islam war lange Zeit von einem religiös-politischen Gegensatz bestimmt, und die zweimalige Belagerung Wiens durch die Osmanen hat sich im kollektiven Gedächtnis niedergeschlagen. Das änderte sich für Österreich-Ungarn durch den Berliner Kongress von 1878, der den russisch-türkischen Krieg gegen die osmanische Herrschaft auf dem Balkan beendete. Im Zuge einer neuen Aufteilung der Gebiete wurde Bosnien-Herzegowina Österreich-Ungarn zunächst zur Verwaltung zugesprochen, etwas später, 1908, annektiert.

Der Weg zur Islamischen Glaubensgemeinschaft

Dieses „Islamgesetz“ ruhte nach dem Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs und der Monarchie, und die Muslime in Österreich konnten sich erst nach dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs wieder in Vereinen organisieren. Aufgrund der zunehmenden Zahl von Muslimen, die in den 1960er Jahren zunächst vor allem als Gastarbeiter nach Österreich kamen, wurde auf der Basis des Gesetzes von 1912 die Einrichtung einer Glaubensgemeinschaft betrieben, zu der es damals noch nicht gekommen war. Dem 1971 gestellten Antrag auf gesetzliche Anerkennung folgten dann nach vielen Verhandlungen mit dem Kultusamt die Genehmigung mit 2. Mai 1979 und die Konstituierung der IGGiÖ.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_in_Austria

http://medienportal.univie.ac.at/muslime-in-oesterreich-100-jahre-islamgesetz

NEWS 18. 06. 2012 http://religion.orf.at/projekt03/news/_iggioe.html

Empfang bei der Nationalratspräsidentin Frau Prammer 18.06.2012

http://www.meineabgeordneten.at/Abgeordnete/Barbara.Prammer

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion orbelief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religionor not to follow any religion.[1] The freedom to leave or discontinue membership in a religion or religious group —in religious terms called „apostasy“ —is also a fundamental part of religious freedom, covered by Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Freedom of religion is considered by many people and nations to be a fundamental human right. In a country with a state religion, freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion, and does not persecute believers in other faiths. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_religion

Kärnten: Interreligiöses Fest anlässlich „100 Jahre Islamgesetz“

Mit einem interreligiösen „Fest des Dialogs“ ist am Samstag in Kärnten das 100-jährige Bestehen des Islamgesetzes in Österreich gefeiert worden. Zum Fest im Klagenfurter Konzerthaus hatte die „Islamische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Österreich“ (IGGiÖ) geladen. Der Kärntner Bischof Alois Schwarz bekundete dabei Dankbarkeit für die „enge Zusammenarbeit“ und das „gute Miteinander“ im Land.

Schwarz erinnerte daran, dass Österreich mit dem Islamgesetz in der Europäischen Union eine Sonderstellung einnimmt. Er empfahl auch anderen Ländern eine solche Regelung. Laut einer Aussendung des Büros von Landeshauptmann Gerhard Dörfler erklärte IGGiÖ-Ehrenpräsident Anas Schakfeh, Österreich könne sich rühmen, mit dem Islamgesetz „Pionier“ zu sein. „Wir honorieren diese Anerkennung mit Loyalität zur Gesellschaft“, so Schakfeh. IGGiÖ-Präsident Fuat Sanac dankte für die Möglichkeit des gemeinsamen Feierns.

„Ich bin Kärntner und Muslim“

Als Kärntner ein Muslim zu sein, sei kein Widerspruch: „Ich fühle mich als Kärnter. Zu meiner Identität gehört auch, dass ich gebürtiger Bosnier bin“, sagte der Präsident der IGGiÖ Kärnten, Esad Memic, laut einem Bericht von „ORF On“. Er fühle sich auch „als Muslim, als Europäer, als Kosmopolit“. All diese Identitäten schlössen einander nicht aus. Ziel sei ein gutes Miteinander: Man sei nicht hier, um die vorherrschende Kultur zu verdrängen, sondern um diese noch „reicher und schöner“ zu machen.

Festredner: Offenheit, Optimismus und Liebe

Der evangelische Superintendent Manfred Sauer betonte beim Fest, Anerkennung und Gleichberechtigung sollten dazu führen, „offen aufeinander zuzugehen und voneinander zu lernen“. Dies gelinge in Kärnten auf eindrucksvolle Weise. Und der Großmufti von Slowenien, Nedzad Grabus, hob hervor, dass man diesbezüglich in Österreich „positiv in die Zukunft schauen“ könne. Landeshauptmann Dörfler betonte in seiner Festrede laut ORF: „Alle Religionen, alle Menschen, alle Ethnien haben dann Platz, wenn sie die Liebe, den Frieden, das Miteinander der Integration und das Verständnis in den Vordergrund stellen.“

Österreichische Muslime schon zu Kaisers Zeiten

In Österreich ist der Islam seit 1912 als Religionsgemeinschaft anerkannt. Das Gesetz sichert Muslimen Selbstbestimmung zu. Eingeführt wurde es, weil mit Bosnien auch rund 600.000 Muslime Teil von Österreich-Ungarn geworden waren. Unter anderem wurde den bosnischen Muslimen in der K.u.K.-Armee dadurch die Betreuung durch Imame ermöglicht.

(KAP)

Veranstaltungen

- Dachgeschoß des Juridicums

- Schottenbastei 10-16

- A-1010 Wien

- 28 Juni 2012

- Islamische Zentrum Wien

- 30 Juni 2012

- 04 Juli 2012

Europasaal, Edmundsburg

Mönchsberg 2, 5020 Salzburg

http://www.facebook.com/IGGiOE

http://www.facebook.com/fuat.sanac

http://www.facebook.com/Islamische-Religionsgemeinde-Salzburg

Background Note

The Challenge of Human Rights and Cultural Diversity

by Diana Ayton-Shenker

The end of the cold war has created a series of tentative attempts to define „a new world order“. So far, the only certainty is that the international community has entered a period of tremendous global transition that, at least for the time being, has created more social problems than solutions.

The end of super-power rivalry, and the growing North/South disparity in wealth and access to resources, coincide with an alarming increase in violence, poverty and unemployment, homelessness, displaced persons and the erosion of environmental stability. The world has also witnessed one of the most severe global economic recessions since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

At the same time, previously isolated peoples are being brought together voluntarily and involuntarily by the increasing integration of markets, the emergence of new regional political alliances, and remarkable advances in telecommunications, biotechnology and transportation that have prompted unprecedented demographic shifts.

The resulting confluence of peoples and cultures is an increasingly global, multicultural world brimming with tension, confusion and conflict in the process of its adjustment to pluralism. There is an understandable urge to return to old conventions, traditional cultures, fundamental values, and the familiar, seemingly secure, sense of one’s identity. Without a secure sense of identity amidst the turmoil of transition, people may resort to isolationism, ethnocentricism and intolerance.

This climate of change and acute vulnerability raises new challenges to our ongoing pursuit of universal human rights. How can human rights be reconciled with the clash of cultures that has come to characterize our time? Cultural background is one of the primary sources of identity. It is the source for a great deal of self-definition, expression, and sense of group belonging. As cultures interact and intermix, cultural identities change. This process can be enriching, but disorienting. The current insecurity of cultural identity reflects fundamental changes in how we define and express who we are today.

Universal Human Rights and Cultural Relativism

This situation sharpens a long-standing dilemma: How can universal human rights exist in a culturally diverse world? As the international community becomes increasingly integrated, how can cultural diversity and integrity be respected? Is a global culture inevitable? If so, is the world ready for it? How could a global culture emerge based on and guided by human dignity and tolerance? These are some of the issues, concerns and questions underlying the debate over universal human rights and cultural relativism.

Cultural relativism is the assertion that human values, far from being universal, vary a great deal according to different cultural perspectives. Some would apply this relativism to the promotion, protection, interpretation and application of human rights which could be interpreted differently within different cultural, ethnic and religious traditions. In other words, according to this view, human rights are culturally relative rather than universal.

Taken to its extreme, this relativism would pose a dangerous threat to the effectiveness of international law and the international system of human rights that has been painstakingly contructed over the decades. If cultural tradition alone governs State compliance with international standards, then widespread disregard, abuse and violation of human rights would be given legitimacy.

Accordingly, the promotion and protection of human rights perceived as culturally relative would only be subject to State discretion, rather than international legal imperative. By rejecting or disregarding their legal obligation to promote and protect universal human rights, States advocating cultural relativism could raise their own cultural norms and particularities above international law and standards.

Universal Human Rights and International Law

http://www.un.org/en/law/index.shtml

Largely through the ongoing work of the United Nations, the universality of human rights has been clearly established and recognized in international law. Human rights are emphasized among the purposes of the United Nations as proclaimed in its Charter, which states that human rights are „for all without distinction“. Human rights are the natural-born rights for every human being, universally. They are not privileges.

The Charter further commits the United Nations and all Member States to action promoting „universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms“. As the cornerstone of the International Bill of Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms consensus on a universal standard of human rights. In the recent issue of A Global Agenda, Charles Norchi points out that the Universal Declaration „represents a broader consensus on human dignity than does any single culture or tradition“.

Universal human rights are further established by the two international covenants on human rights (International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights), and the other international standard-setting instruments which address numerous concerns, including genocide, slavery, torture, racial discrimination, discrimination against women, rights of the child, minorities and religious tolerance.

These achievements in human rights standard-setting span nearly five decades of work by the United Nations General Assembly and other parts of the United Nations system. As an assembly of nearly every State in the international community, the General Assembly is a uniquely representative body authorized to address and advance the protection and promotion of human rights. As such, it serves as an excellent indicator of international consensus on human rights.

This consensus is embodied in the language of the Universal Declaration itself. The universal nature of human rights is literally written into the title of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Its Preamble proclaims the Declaration as a „common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations“.

This statement is echoed most recently in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, which repeats the same language to reaffirm the status of the Universal Declaration as a „common standard“ for everyone. Adopted in June 1993 by the United Nations World Conference on Human Rights in Austria, the Vienna Declaration continues to reinforce the universality of human rights, stating, „All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated“. This means that political, civil, cultural, economic and social human rights are to be seen in their entirety. One cannot pick and choose which rights to promote and protect. They are all of equal value and apply to everyone.

As if to settle the matter once and for all, the Vienna Declaration states in its first paragraph that „the universal nature“ of all human rights and fundamental freedoms is „beyond question“. The unquestionable universality of human rights is presented in the context of the reaffirmation of the obligation of States to promote and protect human rights.

The legal obligation is reaffirmed for all States to promote „universal respect for, and observance and protection of, all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all“. It is clearly stated that the obligation of States is to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights. Not selective, not relative, but universal respect, observance and protection.

Furthermore, the obligation is established for all States, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and other instruments of human rights and international law. No State is exempt from this obligation. All Member States of the United Nations have a legal obligation to promote and protect human rights, regardless of particular cultural perspectives. Universal human rights protection and promotion are asserted in the Vienna Declaration as the „first responsibility“ of all Governments.

Everyone is entitled to human rights without discrimination of any kind. The non-discrimination principle is a fundamental rule of international law. This means that human rights are for all human beings, regardless of „race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status“. Non-discrimination protects individuals and groups against the denial and violation of their human rights. To deny human rights on the grounds of cultural distinction is discriminatory. Human rights are intended for everyone, in every culture.

Human rights are the birthright of every person. If a State dismisses universal human rights on the basis of cultural relativism, then rights would be denied to the persons living under that State’s authority. The denial or abuse of human rights is wrong, regardless of the violator’s culture.

Human Rights, Cultural Integrity and Diversity

Universal human rights do not impose one cultural standard, rather one legal standard of minimum protection necessary for human dignity. As a legal standard adopted through the United Nations, universal human rights represent the hard-won consensus of the international community, not the cultural imperialism of any particular region or set of traditions.

Like most areas of international law, universal human rights are a modern achievement, new to all cultures. Human rights are neither representative of, nor oriented towards, one culture to the exclusion of others. Universal human rights reflect the dynamic, coordinated efforts of the international community to achieve and advance a common standard and international system of law to protect human dignity.

Inherent Flexibility

Out of this process, universal human rights emerge with sufficient flexibility to respect and protect cultural diversity and integrity. The flexibility of human rights to be relevant to diverse cultures is facilitated by the establishment of minimum standards and the incorporation of cultural rights.

The instruments establish minimum standards for economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights. Within this framework, States have maximum room for cultural variation without diluting or compromising the minimum standards of human rights established by law. These minimum standards are in fact quite high , requiring from the State a very high level of performance in the field of human rights.

The Vienna Declaration provides explicit consideration for culture in human rights promotion and protection, stating that „the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds must be borne in mind“. This is deliberately acknowledged in the context of the duty of States to promote and protect human rights regardless of their cultural systems. While its importance is recognized, cultural consideration in no way diminishes States‘ human rights obligations.

Most directly, human rights facilitate respect for and protection of cultural diversity and integrity, through the establishment of cultural rights embodied in instruments of human rights law. These include: the International Bill of Rights; the Convention on the Rights of the Child; the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; the Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice; the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intoleranceination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief; the Declaration on the Principles of International Cultural Cooperation; the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities; the Declaration on the Right to Development; the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families; and the ILO Convention No. 169 on the Rights of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.

Human rights which relate to cultural diversity and integrity encompass a wide range of protections, including: the right to cultural participation; the right to enjoy the arts; conservation, development and diffusion of culture; protection of cultural heritage; freedom for creative activity; protection of persons belonging to ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities; freedom of assembly and association; the right to education; freedom of thought, conscience or religion; freedom of opinion and expression; and the principle of non-discrimination.

Cultural Rights

Every human being has the right to culture, including the right to enjoy and develop cultural life and identity. Cultural rights, however, are not unlimited. The right to culture is limited at the point at which it infringes on another human right. No right can be used at the expense or destruction of another, in accordance with international law.

This means that cultural rights cannot be invoked or interpreted in such a way as to justify any act leading to the denial or violation of other human rights and fundamental freedoms. As such, claiming cultural relativism as an excuse to violate or deny human rights is an abuse of the right to culture.

There are legitimate, substantive limitations on cultural practices, even on well-entrenched traditions. For example, no culture today can legitimately claim a right to practise slavery. Despite its practice in many cultures throughout history, slavery today cannot be considered legitimate, legal, or part of a cultural legacy entitled to protection in any way. To the contrary, all forms of slavery, including contemporary slavery-like practices, are a gross violation of human rights under international law.

Similarly, cultural rights do not justify torture, murder, genocide, discrimination on grounds of sex, race, language or religion, or violation of any of the other universal human rights and fundamental freedoms established in international law. Any attempts to justify such violations on the basis of culture have no validity under international law.

A Cultural Context

The argument of cultural relativism frequently includes or leads to the assertion that traditional culture is sufficient to protect human dignity, and therefore universal human rights are unnecessary. Furthermore, the argument continues, universal human rights can be intrusive and disruptive to traditional protection of human life, liberty and security.

When traditional culture does effectively provide such protection, then human rights by definition would be compatible, posing no threat to the traditional culture. As such, the traditional culture can absorb and apply human rights, and the governing State should be in a better position not only to ratify, but to effectively and fully implement, the international standards.

Traditional culture is not a substitute for human rights; it is a cultural context in which human rights must be established, integrated, promoted and protected. Human rights must be approached in a way that is meaningful and relevant in diverse cultural contexts.

Rather than limit human rights to suit a given culture, why not draw on traditional cultural values to reinforce the application and relevance of universal human rights? There is an increased need to emphasize the common, core values shared by all cultures: the value of life, social order and protection from arbitrary rule. These basic values are embodied in human rights.

Traditional cultures should be approached and recognized as partners to promote greater respect for and observance of human rights. Drawing on compatible practices and common values from traditional cultures would enhance and advance human rights promotion and protection. This approach not only encourages greater tolerance, mutual respect and understanding, but also fosters more effective international cooperation for human rights.

Greater understanding of the ways in which traditional cultures protect the well-being of their people would illuminate the common foundation of human dignity on which human rights promotion and protection stand. This insight would enable human rights advocacy to assert the cultural relevance, as well as the legal obligation, of universal human rights in diverse cultural contexts. Recognition and appreciation of particular cultural contexts would serve to facilitate, rather than reduce, human rights respect and observance.

Working in this way with particular cultures inherently recognizes cultural integrity and diversity, without compromising or diluting the unquestionably universal standard of human rights. Such an approach is essential to ensure that the future will be guided above all by human rights, non-discrimination, tolerance and cultural pluralism.

Published by the United Nations Department of Public Information DPI/1627/HR–March 1995

Comments are closed.