ISLAMIC PLANT MEDICINE AND HISTORY

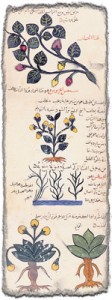

Khawass al-Ashjar, Arabic version of De Materia Medica.

www.islamicmedicine.org/natural.htm

Int. Society for the History of Islamic Medicine

Pedanius Dioscorides (Greek: Πεδάνιος Διοσκορίδης; ca. 40-90) was an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist from Anazarbus, Cilicia, Asia Minor, who practised in ancient Rome during the time of Nero. He had the opportunity to travel extensively seeking medicinal substances from all over the Roman and Greek world. Dioscorides wrote a five-volume book in his native Greek, Περί ὕλης ἰατρικής (De Materia Medica in the Latin translation; Regarding Medical Matters) that is a precursor to all modern pharmacopeias, and is one of the most influential herbal books in history. In fact, it remained in use until about CE 1600. Unlike many classical authors, his works were not „rediscovered“ in the Renaissance, because his book never left circulation. The De Materia Medica was often reproduced in manuscript form through the centuries, often with commentary on Dioscorides‘ work and with minor additions from Arabic and Indian sources, though there were some advancements in herbal science among the Arabic additions. The most important manuscripts survive today in Mount Athos monasteries. DE MATERIA MEDICA is important not just for the history of herbal science: it also gives us a knowledge of the herbs and remedies used by the Greeks, Romans, and other cultures of antiquity. The work also records the Dacian and Thracian names for some plants, which otherwise would have been lost. The work presents about 600 plants in all, although the descriptions are obscurely phrased. Duane Isely notes that „numerous individuals from the Middle Ages on have struggled with the identity of the recondite kinds“, and characterizes most of the identifications of Gunther et al. as „educated guesses“. Read More: > HERE <

Medicine was the first of the Greek sciences to be studied in depth by Islamic scholars. During the ninth century and into the tenth, the spiritual head of Islam, Harun al-Rashid (of Arabian Nights fame), and his son, al-Ma’mun, sent embassies to collect Greek and other scientific works from throughout the region. These were taken to the “House of Wisdom,” where the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegina, Hippocrates, and Dioscorides, were translated into Arabic—manuscripts so important that one of the translators was paid for each translation by its equivalent weight in gold.

Arab pharmacopoeia came from so many sources—as far afield as China, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, southern India, and West Africa—it was enormous. In his second volume of the Canon of Medicine, Ibn Sina (a.d. 980–1037, also known as Avicenna) describes 235 remedies, of which 97 still appear in the official British Pharmacopoeia, as well as 760 medicinal plants and their uses. Ibn Sina also laid out the rules that are the basis of clinical trials today.

Sesam Oil and tamarind not only used in Ayurveda: Like most medieval medicine, the Islamic viewpoint was an outgrowth of Galen’s Humoral Theory and focused on the need to balance the humors, or bodily fluids.

Cathartics, purges, and laxatives were considered essential to this goal. The most popular herb—an enduring favorite today—was senna, a low bush with small yellow flowers, greenish yellow leaves, and fat seed pods. The leaves have a distinctive smell, and the infusion made from them has a nauseatingly sweet taste; taken alone, the infusion does indeed produce nausea. The Arabs calmed both taste and effect by adding aromatic spices.

The Arabs also introduced manna and tamarind as safe, mild, and reliable laxatives. Scammony, a climbing plant of the morning glory family that has thick roots with medicinal value, was a controversial herb in Europe, where some practitioners declared its violent laxative action unsafe to use under any conditions, while others said they could not function without it. Islamic pharmacists responded by devising a reliable preparation to temper the herb’s ferocity but retain its potency. They did this by first boiling the scammony root inside a fruit called a quince; the scammony was then discarded and the quince pulp mixed with the soothing, gooey seeds of psyllium. The preparation was known as “diagridium.”

Formulation developed into an art involving many steps and ingredients. Ar-Razi, Islamic medicine’s greatest clinician and most original thinker, combined bitter almonds with an ounce of raisin rob, or pulp, to treat kidney stones. For the same ailment, a clinician named Haly Abbas recommended boiling jujubes, fruits of sebesten, white maude, and seeds of smallage, fennel, caltrop, and thyme.

In addition to compounds, the Arabs valued hundreds of simple herbal remedies. They used sesame oil to relieve coughs and soften rawness of the throat. Juice from the stalk and leaves of the licorice plant was considered good for respiratory problems, swollen glands, and clearing the throat, whereas the root was used to treat foot ulcers and wounds.

Myrrh, primarily known in the West as a gift from one of the Three Wise Men, was highly valued for its medicinal properties as an astringent and was also used to treat dyspepsia, chronic bronchitis, leukorrhea, and as a topical application in gum disease. In fact, it is a primary ingredient in many commercial mouthwashes today.

An Ancient Tradtion survived: Arab pharmacology was not only extensive but also the strongest empirically based biological science. Ibn Sina’s Canon laid out the basic rules of clinical drug trials, ones that are still followed today: A drug being tested must be pure, and it must work on all cases of the disease. Testing in humans, with careful notation of the drug’s effectiveness under different conditions, was the necessary final step. Observation and experimentation were the sole determinants of the value (or lack of value) of a potential treatment.

Not surprisingly, when Europe began to stir from a thousand years of intellectual slumber, it turned to the Islamic world. It was no coincidence that Salerno, Europe’s first great medical center, was close to Arab Sicily, or that the first outstanding medical university, Montpellier, was located in southern France, near the Andalusian border.

Comments are closed.